A Healthy Model in Hard Times

Many younger Christian leaders of color have become frustrated with how some evangelicals promote racial reconciliation with their words while devaluing authentic reconciliation with their deeds.

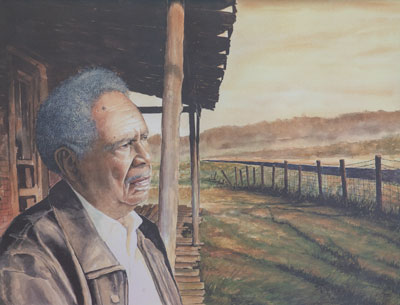

“The Reconciler – The Road to Freedom” by Mark McFerron, markmcferron.com

These disillusioned saints are beginning to abscond from predominantly white Christian organizations that refuse to acknowledge racial hierarchicalism’s constitutive elements — white structural advantage, white normalization and white transparency. Each of these elements refer to the social construction of race-based structures that keep Christian image-bearers from achieving the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace (Eph. 4:3).

My primary concern for racial reconciliation will always be threefold: missiological imperative, eschatological vision and spiritual friendship as a means of grace.

Jesus Christ commands His friends to make disciples of all nations. – Matt. 28:16-20; John 17:21

God revealed the eternal worship service of every tribe and nation on one accord bowing their heads to the risen lamb of God who was slain before the foundation of the world. – Rev. 5:9; 7:9

Biblical trinitarianism models deep-seated communal love and loyalty within the Godhead which undergirds our commitment to glorify God by evangelistically loving one another. – John 17:21

We need models who exude a long obedience in the same direction.

A healthy model

When I read spiritual theology, I typically breathe a prayer of thanks for the faithful men and women who championed gospel-centered racial reconciliation when it was not in vogue. They have gone the distance without seeing a considerable amount of multiethnic fruit throughout Baptist churches in the Commonwealth; nevertheless, they did not lose hope.

Rev. Lincoln Bingham is a fine example.

In the Kentucky Baptist Building, there is a mural dedicated to the historic development of our cooperative missions partnership in Kentucky. The timeline expands from the first days of Squire Boone II, brother of Daniel Boone, who became the first Baptist preacher to enter Kentucky in 1769, to the unprecedented 2015 election of Kev-in Smith, the first African-American KBC president. These wonderful pictures reflect KBC “stones of remembrance” or a prophetic “hall of faith.” They remind Kentucky Baptists since God was at work then, and “God is at work now,” we know that our labor together is not in vain (John 5:17; 1Cor. 15:58).

Whenever I depart the executive suite, I encounter the portrait of Rev. Lincoln Bingham, positioned just past the middle of the timeline, just across the hall from the doorway. The mural’s dedication to Rev. Bingham reads, “(In 1976) the Kentucky Baptist Convention forms the Department of Interracial Cooperation to promote close and more effective cooperation between white and black Baptists in Kentucky.”

The picture of Rev. Bingham whispers to every Kentucky Baptist who tours the building, taking time read and reflect on our legacy, in a world polarized by mistrust and racial strife, “not to get tired of doing good, for we will reap a harvest if we don’t give up” (Gal. 6:9). Lincoln Bingham is a healthy model in hard times.

Curtis Woods is interim co-executive director of the Kentucky Baptist Convention.

Curtis Woods