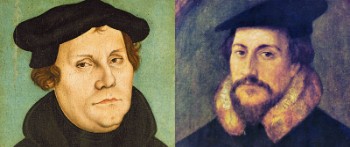

Five hundred years ago, on Oct. 31, 1516, Martin Luther was a German Catholic priest questioning whether the pope truly had power to spring souls from purgatory. John Calvin was a 7-year-old in France who had just reached what medievals deemed the “age of accountability.” In the Netherlands, Menno Simons was a 20-year-old headed toward the Catholic priesthood who had never read the Bible.

A year later, Luther would nail 95 theses to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany, challenging some of the Roman Catholic Church’s practices and sparking a movement that changed all three men’s paths forever. The challenges of Luther and others eventually provoked the Catholic Church to correct corrupt practices among some clergy. Later, Luther began challenging fundamentals of Catholic doctrine and separated definitively from Rome.

But on the previous Oct. 31, Luther, Calvin and Menno were merely historical soil in which the seeds of the Reformation were about to sprout.

“The Reformation happened at a great kairotic turning point in history,” Reformation scholar Timothy George said, referencing the Greek word “kairos,” which signifies an opportune moment that is either seized or lost. “It was the end of one era and the beginning of another” with “a lot of changes in the wind.”

George, author of “Theology of the Reformers” and dean of Samford University’s Beeson Divinity School, told Baptist Press some hints of the change to come were evident in the lives of Luther, Calvin and Menno in 1516.

With Luther, change was clearly on the horizon. Calvin and Menno were still nearly two decades away from becoming Protestant Reformers, but their lives illustrated some prominent flaws of medieval Catholicism that they eventually came to criticize.

Martin Luther

Then a 32-year-old monk, Luther was preparing for a special event on Oct. 31, 1516. The next day, the pope had granted the Castle Church in Wittenberg the privilege of dispensing the supposedly excess merit of Jesus, Mary and the saints to those who viewed the local collection of relics—which supposedly included pieces of Mary’s girdle and a strand of Jesus’ beard, according to Roland Bainton’s book “Here I Stand.”

Receiving the allegedly excess merit was said to decrease a soul’s time in purgatory, a place where Catholics claim people receive punishment for certain types of sins before being released to heaven.

The whole practice, known as granting indulgences, seemed suspect to Luther, and he said so in a sermon.

“Luther spoke moderately and without certainty on all points,” Bainton wrote of Luther’s Oct. 31, 1516, sermon. “But on some, he was perfectly assured. … To assert that the pope can deliver souls from purgatory is audacious. If he can do so, then he is cruel not to release them all.”

Luther, who later rejected the doctrine of purgatory altogether, was particularly sensitive about absolution of sin because of his own intense struggle with guilt.

Though not a particularly noteworthy sinner by Bainton’s account, Luther found it impossible to do enough good works to satisfy God’s moral standards. He would confess his sins to a mentor priest daily—for six hours on at least one occasion—leading his mentor to say, “If you expect Christ to forgive you, come in with something to forgive—parricide (murder of a relative), blasphemy, adultery—instead of all these peccadilloes.”

George thinks Luther had found the spiritual relief he sought by 1516, receiving Christ as Lord and Savior by faith alone. But he had not yet articulated his mature doctrine of justification by faith alone. That would come two or three years later.

On Oct. 31, 1516, however, his discontentment with the spiritual status quo was already coming through.

John Calvin

Not as much is known about what Calvin was doing specifically on that day. After his mother died when he was five or six, Calvin was raised by “friends of the family … of the noble caste in France,” George said.

As part of a Catholic family, Calvin would have received infant baptism and been required to take communion at least once a year. One of the few episodes known from Calvin’s early childhood, according to “Theology of the Reformers,” is that his mother once took him to kiss what was purported to be the severed finger of St. Anne, the alleged mother of Mary.

Beginning around 1516, Calvin would have begun to appear before a priest to answer what George called “guilt-inducing” questions about his own sins.

Among the types of questions seven year olds faced, according to “Theology of the Reformers”: “Have you believed in magic?” “Have you failed to kneel on both knees or remove your hat during communion?” “Have you thrown snowballs or rocks at others?” And just to make sure the child was paying attention and not answering mindlessly: “Did you kill the emperor with a double-headed ax?”

Preaching of the day, Calvin later wrote, “informed us we were miserable sinners dependent on thy mercy; reconciliation was to come through the righteousness of works.”

By age 12, Calvin secured a benefice, a church office that would pay him for life while requiring little of him. To perform the few duties required, Calvin’s family would have hired an illiterate common priest, George said, noting the setup was typical of medieval church life.

Though Calvin came to reject the medieval Catholic system and became a leading voice for Protestantism by the mid-1530s, there was little hint in 1516 that he would make that dramatic turn.

Menno Simons

The situation was similar in 1516 for Menno. Though he went on to become a leading Anabaptist—rejecting infant baptism, advocating the church’s freedom from government control and drawing harsh criticism from so-called Magisterial Reformers like Luther and Calvin—he was a “typical Catholic” at age 20, George said.

Among his typical characteristics was Menno’s level of biblical illiteracy. While he could read both Latin and Greek, becoming what George called “an above average Catholic priest” in 1524, Menno claimed not to have read the Bible until approximately 1526.

The Catholic Church later would work to remedy the lack of education among priests as well as moral shortcomings like the benefice system Calvin encountered.

Also in the mid-1520s, Menno began to question whether the bread and wine of communion really transformed into the body and blood of Christ as the Catholic Church taught. It wasn’t until 1535, however, that witnessing the slaughter of a group of “misled,” violent Anabaptists inspired Menno to receive Christ as his Lord and Savior and become an Anabaptist himself—though one dedicated to pacifism.

Yet in 1516, there was little hint of that coming transformation or of Menno’s significant leadership that would eventuate in Dutch Anabaptists’ being called “Mennonites.”

Reformation context

“It’s a great mistake to think that the Reformation just kind of happened do novo out of nothing,” George said.

“There was a context,” he continued, of people like Luther, Calvin and Menno, who wanted to “purify the church” and “reform the church” as it existed in 1516. (BP)

David Roach